Red Mirage Questions

- 1 Why do mail ballots take longer than in-person ballots to count?

- 2 What are the specific election laws that determine how fast/slow a state will be able to count their mail ballots?

- 3 What states are likely to be fast counting states? What states will be slow? Why?

- 4 Has there ever been a red mirage/blue shift in a previous Presidential election?

- 5 How will President Trump react to a “red mirage” on election night?

- 6 Who is responsible for “calling the race” (announcing a projected winner) during Presidential elections? Will the red mirage influence when the race is called?

- 7 Can we project who will win the 2020 election based on the Early Vote? If not, what conclusion(s) can we make based on the Early Vote?

Voting Questions

- 1 Does each state set their own rules for how elections are conducted?

- 2 How can someone vote before election day?

- 3 What is absentee voting?

- 4 What is early voting?

- 5 For the upcoming Presidential election, is there some form (early voting or in-person absentee) of early in person voting in every state?

- 6 What is “vote by mail”?

- 7 What is the difference between vote by mail and absentee voting?

- 8 Can anyone vote absentee by mail?

- 9 COVID-19 Impact

RED MIRAGE

Why do mail ballots take longer than in-person ballots to count?

There are three general reasons why mail ballots may take longer to count than in-person votes:

1. State election laws

This is the most important factor in determining how long it will take a state to count/process ballots on election day — some states allow for processing to begin upon receipt of a ballot or weeks before election day, while others do not allow for any sort of early processing before November 3rd. In addition, some states (including Ohio, North Carolina, Pennsylvania) accept “late” ballots: even if a ballot is received after Nov. 3 it may still be counted long as it is received by the post election day deadline set by the state (usually 2-7 days after in most instances) and the ballot is postmarked on or before Election Day. Moreover, several states allow voters to “cure” ballots— aka fix errors on their absentee ballots that have been sent in and received by the election office — which can also drag out the process if states allow for curing after election day. In Ohio, for example, voters have up to a week to fix their ballots after election day.

See a more in depth explanation of key state election laws below.

2. States’ prior experience with by mail voting and the amount of resources dedicated to election administration.

States that are accustomed to handling large numbers of mail ballots, and have the requisite staff and modern equipment, will be in a much better position to avoid potential pitfalls that may plague less experienced, under-equipped states.

3. Mail ballots take longer for workers to process than in person votes.

Although states differ in their exact policies, counting mail ballots often involves time intensive procedures such as verifying signatures and opening/sorting envelopes. This will obviously be particularly relevant in states that are expecting a record number of mail votes but have little time to process them before election day (ex: PA).

What are the specific election laws that determine how fast/slow a state will be able to count their mail ballots?

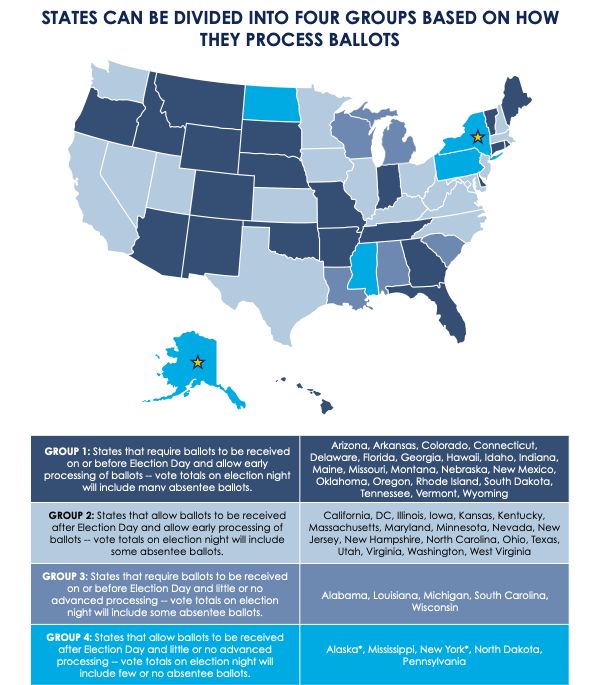

Election laws governing when processing/counting of mail ballots may begin, how long voters have to remedy ballot errors, and the final deadline set for accepting mail ballots are the most important factors in determining how long it will take a state to declare a winner. We can break up these considerations into two separate camps: pre-election day and post-election day state rules.

Pre-election day

Processing/Counting of Ballots

What is processing?

After a voter’s mail ballot is received by a local elections office, it must then be processed. Processing is a vague term but essentially refers to the preliminary procedures — such as verifying signatures and removing the mail ballot from its envelope, etc. — taken by administrators before the ballot can actually be counted. Processing rules may vary by state — some allow for administrators to do basically everything except count the ballot as part of their “processing”, while others only allow for verifying signatures. A full list of every states’ processing policies can be found here.

When can processing begin?

It depends! Some states allow for processing to begin whenever the mail ballot is received, others allow for early processing but set a firm date on when such activity can commence (ex: “two weeks before election day”) , and some do not allow for any processing before election day.

The impact of enabling election administrators to start processing ballots before election day is pretty simple — it saves a lot of time and therefore dramatically increases the likelihood that a state will be able to tally all of its votes on election night.

What about counting?

After a mail ballot is successfully processed, the ballot may then be counted. However, this is not necessarily a continuous exercise that immediately follows processing — while some states have the same start date for counting and processing, others do not. For example, some states that authorize early processing do not allow for counting until election day, so after a ballot is processed in such states, there is essentially a waiting period before the ballot can actually be counted. To be clear, in all states that allow for early counting, no results may be released before election day.

Also, it should be noted that if a state permits extensive processing ahead of time — in which the ballot is fully “teed up” for tabulation — counting won’t take very long. The processing of mail ballots is what makes mail voting a more time intensive undertaking for election administrators vs. handling in-person ballots. Nonetheless, states that allow for both early processing and early counting will have the fastest returns.

Post-election day

The other major consideration for how long it will take a state to count all of its votes is whether the state allows for how it regulates voting activity after November 3rd.

1) Hard or Soft Deadline for Mail Ballots?

Hard deadline = when polls close on Election Day; Soft deadline = may be received after election day

States have different rules about the deadline for when they must receive mail/absentee votes.

Some states have laws that set election day as the deadline for receiving mail ballots — in these “hard” deadline states, any mail ballot received after November 3rd, regardless of when they were sent, will not be counted.

Ex: In a hard deadline state, even if you mail a ballot in before election day, if it is not received

However, other states will count mail ballots that are received after election day if they are postmarked on or before election day.

For example, in a state where mail ballots will be accepted five days after the election as long as the ballot is postmarked by election day, if a mail ballot is postmarked November 2, but is not received until November 5 it will still count.

However, in other states with hard deadlines (see above), a ballot received after November 3rd (election day) will not be counted — even if it is sent before election day.

States differ on how many extra days they will permit ballots to be accepted past election day. Most allow somewhere between 2-5 days, but the spectrum runs from 1-14 days.

See a full list of states’ postmark policies here (NOTE: this list may be outdated for certain states involved in recent litigation on this issue)

Fears that a significant number of mail ballots will NOT be counted because they are received too late has been a source of particular concern this year due to the controversial reforms made by Postal Service General Louis DeJoy. Specifically, DeJoy’s “restructuring” of the postal service: “slowed delivery, removed high-speed letter sorters from commission, [ended the policy of having] mail-in ballots be automatically moved as priority mail, reduced post office operating hours across several states, cut overtime for postal workers and removed some of their iconic blue letter collection boxes.” This attempt to undermine the efficiency of the Postal Service ahead of an anticipated surge in mail ballot activity was interpreted by many as a political attempt to disenfranchise voters.

So if voters want to ensure that their mail in vote actually counts, they should send them in as early as possible. The USPS recommends voters allow one week between when they request their ballot and when they would like to receive it, and another week between when they put their completed ballot in the mail and the state’s deadline for receiving it.

For a comprehensive record of when voters in each state should request and send back their mail ballots, according to USPS guidelines, and how different that is from each jurisdiction’s deadline see FiveThirtyEight’s list here

2) “Curing” Mail Ballots — This refers to voters ability to fix errors on submitted ballots.

In terms of vote counting speed, states that allow for curing after election day may take longer to get a final count in.

18 states legally require their election officials to notify voters that there is a problem with the mail ballot they submitted, and allow these voters to correct the error so their vote may be counted (instead of being invalidated). Notably, these states differ in how much time they provide voters to “cure” their ballot — some set election day as a cutoff while others allow these voters up to two weeks after the election to fix any errors.

It’s also important to note that this issue has been and will continue to be a highly litigated subject in the 2020 Presidential election in many key swing states.

According to NPR: “in the 2016 presidential election, 318,728 mail-in ballots were rejected, largely because of signature problems and missed deadlines. But many more voters are voting by mail this year because of the coronavirus pandemic, raising the possibility of many more rejections. An analysis this year found that more than half a million mail-in ballots were rejected in this year’s primaries.”

What states are likely to be fast counting states? What states will be slow? Why?

FAST

A state’s election laws related to processing/counting start dates and postmark deadlines are the most important factors in determining whether a state will be fast or slow counting. States that allow 2+ weeks for processing ahead of election day and do not accept ballots received after election day will likely have results on election night in 2020.

SLOW

States that do not allow for processing of mail ballots until election day and accept late ballots (postmarked by election day) are categorized as the slowest states. These states will probably not have a projection on election, and will likely take 2-3 days to count all of its mail ballots. See swing states ranked tiers three and four below:

The Senate Democrats created a ranking system that assigned states to four groups based on their expected speed (with 1 being the fastest, 4 the slowest), which include the following swing states:

Group 1— Fastest: AZ, FL, GA

Group 2 — Fast: NV,* NC, OH, TX

Group 3 — Slow: MI, WI, MI

Group 4: — Slowest: PA

Has there been a red mirage/blue shift in any recent Presidential election?

Yes. In Explaining the Blue Shift in Election Canvassing, Professors Edward B. Foley and Charles Stewart III identify five previous presidential elections in which there was a “net partisan gain” as a result of the votes counted after election day since 1948:

· 1960: 0.20% in favor of Nixon

· 2004: 0.12% in favor of Kerry

· 2008: 0.35% in favor of Obama

· 2012: 0.39% in favor of Obama

· 2016: 0.30% in favor of Clinton

Foley and Stewart attribute the increase in frequency of these “shifts” to the overall growth of provisional and mail voting since 2000. Moreover, they note that Democrats are more likely than Republicans to cast provisional ballots, and that while the two parties have similar historical rates of mail voting, Democrats “pulled slightly” ahead in this category in 2016.

However, given the extraordinary and unprecedented number of voters using mail ballots this year, looking to previous election results is not an especially useful resource in predicting the size or significance of a potential red or blue shift in 2020.

How will President Trump react to a “red mirage” on election night?

Some election experts and political commentators believe that a red mirage will embolden President Trump to double down on his claims that the Democrats have “stolen the election”, and/or lead him to declare victory “prematurely” before any major networks call the race.

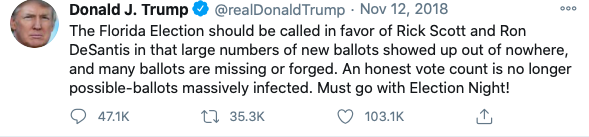

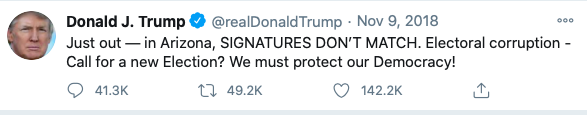

Trump has tweeted countless times about his belief that voting by mail is “fraudulent”, “corrupt”, and the “scandal of our times”. Mainstream news outlets’ fact checkers have found these claims to be without evidence. Furthermore, the President’s reaction to two high profile midterm races in AZ and FL that were plagued by delays and featured lead “shifts” as all the mail ballots were tallied may serve as a sort of “precedent” for his likely behavior on election night.

- President Trump blamed “electoral corruption” (without evidence) for Kyrsten Sinema’s (D) comeback victory over Martha McSally (R) in AZ’s 2018 Senate race. The latter was leading on election night but had her lead slip away as all the votes were counted over the next week.

- Trump also sought to cast doubt on the outcomes in Florida’s 2018 Gubernatorial and US Senate races — claiming (without evidence) that a “large number of new ballot showed up out of nowhere and many ballots are missing or forged. An honest count is no longer possible — ballots massively infected. Must go with Election Night!”. Ultimately, Scott (R) and DeSantis (R) both ended up winning their respective races, not because election officials decided to heed the President’s advice and “go with election night” results, but rather because they each had more votes than their opponents when all the ballots were counted.

UPDATE (11/1): According to a report from Axios:

“President Trump has told confidants he’ll declare victory on Tuesday night if it looks like he’s “ahead,” according to three sources familiar with his private comments. That’s even if the Electoral College outcome still hinges on large numbers of uncounted votes in key states like Pennsylvania” […] Trump has privately talked through this scenario in some detail in the last few weeks, describing plans to walk up to a podium on election night and declare he has won […] For this to happen, his allies expect he would need to either win or have commanding leads in Ohio, Florida, North Carolina, Texas, Iowa, Arizona and Georgia.”

To be clear, Trump’s declaration of victory would be purely symbolic — it would have no actual legal significance. More than anything else, it would represent a self-serving attempt to manipulate public opinion and sow doubt about the “legitimacy” of the election. As Richard Hansen points out in his article “Trump Can’t Just “Declare Victory,” although there have been a number of legal challenges related to whether states should be able to receive absentee ballots (that are postmarked before or on election day) after November 3rd, “there has never been any basis to claim that a ballot arriving on time cannot be counted if officials cannot finish their count on election night […] such a claim is preposterous because no state fully counts their ballots on election night. Many states allow military ballots to arrive for days after Election Day. Counting generally continues for days and weeks after Election Day, and results are not certified until weeks after. When it comes to the president, the presidential electors do not cast their official ballots until Dec. 14, and Congress does not count their votes until Jan. 6. This calendar leaves plenty of time to get the counting done”.

In short, by prematurely declaring himself the winner of the election, Trump would seek to disenfranchise tens of millions of Americans who have legally cast perfectly valid ballots. Putting aside the fact that this sort of behavior would be completely unprecedented, incredibly misleading, and profoundly irresponsible, Trump simply does not have the power to override state election law and set arbitrary counting deadlines that benefit his own electoral prospects.

Who is responsible for “calling the race” (announcing a projected winner) during Presidential elections? Will the red mirage influence when the race is called?

There is not a formal government entity that officially projects a winner of our Presidential elections. (Note: see more on the official “certification” process here). Rather, media organizations each use exit poll data, actual returns, and their own analysis to decide when a state will be called for a candidate, and then ultimately call the entire race when a candidate has won enough states to meet/exceed 270 delegates ( and thereby clinch electoral college victory).

2020 will provide additional challenges for these media organizations tasked with deciding when to call a given state, much less the entire race. As the Washington Post notes, “the major networks and the AP will be under extra pressure not to contribute to a national crisis with a premature call. The supersized number of mail-in ballots, and the chance of a “big blue shift,” will be one factor they’ll have to consider.” Specifically, the historic levels of early voting will create new dynamics that these networks will have to account for based on each state’s unique voting laws and counting speed.

For example, a state like Pennsylvania — expected to have a considerable amount of its election day votes, but very few of its absentee votes, counted on election night — will demand a great amount of patience (may take several take days) to allow for all of its mail ballots to be counted. The pressure to call a state in line with a traditional timeline (per NY Magazine: “with the exception of the infamous 2000 contest, we’ve known the winner of every presidential election in this and the last century by the day after Election Daywe’ve known the winner of every presidential election by the day after Election Day except for in 2000“) will only be exacerbated by the skewed partisan tilt of mail vs. election day in person votes. For example, the PA early returns will look quite encouraging for President Trump, and to the unknowing observer, may appear that he is set to coast to victory early on. However, networks will have to wait until a sufficient number of mail ballots (skewing in favor of Biden) to be counted to make a conclusive determination on the state of the race.

To be clear, decision desks are well aware of the unique issues related to this election and have expressed their intention to be extremely cautious in their approach this year. Given that 82% of US adults have confidence their main news sources will make the right call, these media organization will play a critical role in conveying accurate, fact based information and reducing any potential chaos during election night/(week).

Can we project who will win the 2020 election based on the Early Vote? If not, what conclusion(s) can we make based on the Early Vote?

No, the early vote alone shouldn’t be relied upon to predict of who will ultimately win the election. While the record breaking levels of early voting is certainly a great sign for Democrats and overall turnout in 2020, and Republicans will certainly need a great turnout on election day to catchup if they want to hold the Senate/Presidency, there’s a lot we still don’t know. CNN’s Harry Enten explained this dynamic:

“You should be very careful trying to translate early and absentee voting statistics into trying to understand whether President Donald Trump or former Vice President Joe Biden is going to win the presidential race […] The issue is that we really don’t know the extent to which the early vote will be more Democratic-leaning than the overall tally. There’s no history of early voting during a pandemic. Moreover, just because we know the party affiliation of the voters returning ballots in some states doesn’t mean we know they’re voting for […] When you look at early ballots, you’re missing a lot of context. Mainly, you have no idea who is going to turn out on Election Day[…] None of this is to say early voting statistics are useless. They’re telling us that the polls seem to be on the right track. There are a lot more people voting early than ever before, and these folks tend to be Democrats. Moreover, they heavily suggest that Trump’s rhetoric decrying mail voting seems to have kept Republicans from voting by mail.”

VOTING

Does each state set their own rules for how elections are conducted?

Yes — each state has its own laws pertaining to election administration, so there are differences in both substantive policies (ex: counting/processing, “cure”, postmarked ballots deadlines, etc.) and vocabulary used to describe their respective (but often similar) voting processes. Unfortunately, this can make things confusing, but hopefully the answers below will help clarify the most basic and important elements of how our electoral system works!

How can someone vote before election day?

Although specific policies differ by state, the two main programs for voting before election day are: 1) early voting; 2) absentee voting (in-person or by mail)

What is absentee voting?

Absentee voting allows registered voters to vote by mail or vote in person during a designated period before election day, instead of going to their polling place and voting on election day. Below is a brief description of the two main types of absentee voting

1) Absentee by Mail → Registered voters may request to have their ballots sent to them in the mail, which they then can fill out, and then return by mail or in person to their local elections office. Some states also allow voters to return their absentee ballot to “dropboxes” as well.

2) In-person Absentee → Voters visit the local elections office to request an absentee ballot application. At the elections office, voters complete the application and fill out their ballot in person.

Note: In 2020, sixteen states do not have “early voting” but do have in-person absentee. In these states, voters must go to their local voter registration/election office, fill out an application, and then they may cast their ballot while there in person.

What is early voting?

Early voting allows registered voters to vote in-person at designated locations before election day. You do not need any excuse for “early voting”. Early voting is essentially equivalent to voting on election day, but just takes place earlier!

For the 2020 Presidential election, 25 states and D.C. are set to hold traditional early voting at polling places or vote centers. Early voting periods vary by state, and even when a state may offer early voting, the dates and times may differ for various counties within the state. In general, early voting begins around three weeks before the election and ends during the week before Election Day.

A list of states that offer early voting, and the designated periods when locations will be open for voters in the state can be found here.

For the upcoming Presidential election, is there some form (early voting or in-person absentee) of early in person voting in every state?

No. Nine states do not have in-person early voting. However, the overwhelming majority of states will offer some sort of in-person early voting option — “25 states and D.C. are set to hold traditional early voting at polling places or vote centers, 16 states will allow voters to cast their ballots early at their local election offices, and nine states”.

What is “vote by mail”?

Vote by mail generally refers to the practice of sending out mail ballots to all registered voters in the state automatically. No application is required by the voter; they are sent an absentee mail ballot and can return back via the mail, or by dropping off in person at their election office or official dropbox location. States where mail-in ballots are automatically sent to all voters in this upcoming election include: Hawaii, Oregon, California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Washington, Montana*, Vermont, New Jersey, and Washington DC.

However, the phrase “vote by mail” can also be used in reference to non-universal mail voting programs like in Florida, where residents must send in an application for an absentee ballot, but the state officially refers to this as “vote by mail” rather than “absentee voting”. Moreover, “vote by mail” is also often used informally as a catch all term for the practice of sending in ballots by mail.

What is the difference between vote by mail and absentee voting?

The key difference is that in “vote by mail” states (ex: Utah, Oregon, Washington, etc.), all registered voters are automatically sent a ballot.

In states that use traditional absentee voting, registered voters must send in an application for an absentee ballot — the state does NOT automatically send them a ballot simply because they are a registered voter.

Can anyone vote absentee by mail?

Every state today provides the option for absentee voting; however, states differ on whether a state approved excuse is necessary to obtain an absentee ballot.

Some states only allow voters who can provide a state approved “excuse” (ex: illness, out of state during time of election, etc.) for their inability to vote at their polling place on election day to vote absentee. However, other states have expanded on this concept, and now allow for “no-excuse” absentee voting — which, as the title suggests, enables any registered voter to request an absentee ballot.

To be clear, both excuse and no-excuse absentee voting states require a registered voter to submit an application to vote absentee — the key difference is that in no-excuse states, voters do not have to provide a state approved reason on their application for voting absentee. In excuse states, voters must select a state approved reason for voting absentee on their application, and if they do not fall under one of those reasons, they cannot vote absentee.

COVID-19 Impact

Many states that previously required an excuse have recently changed their election laws — either permanently or temporarily — for the upcoming 2020 Presidential election to allow all registered voters to vote absentee (NOTE: for this cycle, the same dynamic applies to states’ where COVID-19 universally applies to all voters’ as a “legitimate excuse”). Below is a summary of the updated status of where states stand on voting absentee for the 2020 Presidential Election.

The Brookings Institute put together a grade rankings list for all 50 states based on how prepared the state is to vote in a pandemic. See the full list here.